STAUNTON — It’s about a two-mile hike from the house on Lambert Street to what was then Booker T. Washington High School on West Johnson. Claudia Strother Gaines remembers it seemed like a long walk as a teenager, especially in the winter with the cold, biting wind fighting her with every step.

Every now and again Gaines would get fortunate when one of her teachers would drive by, stop and give her a ride the rest of the way. If that didn’t happen, Gaines would make the 45-minute walk to school in the morning and back home in the afternoon.

It was the early 1960s. Gaines was the oldest of four children living with their parents, Wilbur and Catherine Strother, in the Shea House on Lambert, right next to Fairview Cemetery across from what is now the city’s main post office. Her bedroom was upstairs with a window facing west and overlooking the cemetery.

“It was very eerie, to be a teenager living right beside the cemetery,” Gaines recently told The News Leader by phone from her Maryland home. “Sometimes during the night, 10 or 11 o’clock if I was upstairs doing homework or something, I’d look out the window. It was one little window up there. Cars would park up there and I’d be amazed that they would come to a scary cemetery.”

Not everyone in her family must have felt it was eerie. She said the Strothers had a lot of family in Staunton, and Gaines clearly remembers when they’d come over to the Shea House for cookouts in the big backyard. She doesn’t remember anyone thinking it was odd to be socializing right next to a graveyard.

The property itself was beautiful, Gaines said. Her dad was a wonderful gardener, planting vegetables out back and flowers in both the front and back yards. The wide front porch was under a roof, with cast-concrete steps centered on the porch opening.

There was a giant black walnut tree in the front yard. Every autumn when the walnuts would fall to the ground, relatives and others in the neighborhood would ask permission to pick them up. Gaines said keeping the yard free of black walnuts was never a problem. Everyone wanted to get them.

“At that time black walnuts were hard to come by,” she said, “and they were exorbitant as far as prices are concerned.”

Saving Shea House

The Shea House was built in 1876 as a private home for Edward and Bridget Shea, Irish immigrants who shared the five-room, 1,058 square-foot Folk Victorian cottage with their eight children.

Edward Shea died in May 1890. Ten years later, on Dec. 12, 1900, a deed was drawn up for $875, between Bridget Shea and the trustees of Augusta Street Methodist Episcopal Church and Mount Zion Baptist Church to purchase the land held by the Sheas. The two churches owned the adjoining Fairview Cemetery, Staunton’s largest African-American cemetery, and the house became part of the property. At times Shea House has been the home of the cemetery’s caretaker.

It is currently in disrepair, though, and The Staunton-Augusta County African American Research Society and the Fairview Cemetery Committee are working to save it, starting with a fundraiser that kicks off Saturday, June 22 from 10 a.m. until noon at Augusta Street United Methodist at 325 N. Augusta.

The community is invited to stop by anytime during the event to purchase some raffle tickets and baked goods, and bring a monetary donation to help repair the Shea House. There will also be short presentations and vision boards for the project.

Susie King, a member of the committee, said this is just phase one of the project to restore the house. It will focus on repairs to the foundation and installation of new gutters. Phase two includes repairs to windows, installation of a new electrical system and insulating the walls. Repair of the floors, renovation of the bathrooms and kitchen and plumbing upgrades will come in phase three, while phase four will see a new front porch and sidewalk installed.

King said in addition to asking the community to help through fundraising and volunteer efforts, there is also work underway to obtain grant money to help with the restoration. King said once complete, the restored Shea House will be used as a research and administrative building for the cemetery.

Historical Fairview Cemetery

Fairview was acquired from a local farmer in 1869 for $1,200 by Augusta Street United Methodist Church and Mount Zion Baptist Church as a burial ground for members of the two churches. A historical marker says there are more than 2,000 grave sites in the cemetery. Historians said there could be as many as 3,000 with an unknown amount of unmarked graves in the six acres of land, including a pauper’s burial area near the cemetery’s entrance.

Willis Carter is one of the more notable people buried at Fairview. A former slave born in Albemarle County, Carter went on to become a teacher and principal in Staunton’s African American schools, editor of the “Staunton Tribune,” and an activist in the Republican Party. Robert Heinrich and Deborah Harding’s “From Slave to Statesman,” tells his story. Through Harding’s research it was discovered that Carter was buried in Fairview with his wife.

That’s just one of the many fascinating people buried there.

“This cemetery and the history of the people who have been laid to rest there is quite significant,” said Mary Baldwin University professor Amy Tillerson-Brown.

“While we see the name and the date of birth and date of death, what we’re teasing out from that is what’s going on in that dash,” Tillerson-Brown said. “We’re interested in those stories because that’s what paints a picture of this community.”

Tillerson-Brown is part of a committee called the Friends of Fairview, a volunteer group that was working to study and preserve the history of the cemetery. At some point in the process, Tillerson-Brown said some members of the churches became concerned that they might lose control of the cemetery. The group decided to remain involved, but from afar, leaving the churches to deal with the property,

“We’re still interested, we’re still grabbing stories, we still want to make certain that the history is preserved and it’s kept up,” Tillerson-Brown said. “We are often still in the loop, even with these contemporary efforts.”

Keeping history alive

Louisa Dixon is also a member of Friends of Fairview. She remembers seeing a quote that is important to remember when talking about preserving Fairview.

“You can know the true sign of a society in the way they treat their dead,” Dixon said.

It’s important to keep the history alive for future generations because many who know the history or have studied the history of Fairview Cemetery and Staunton’s African-American community are getting older, as are the congregations of both churches.

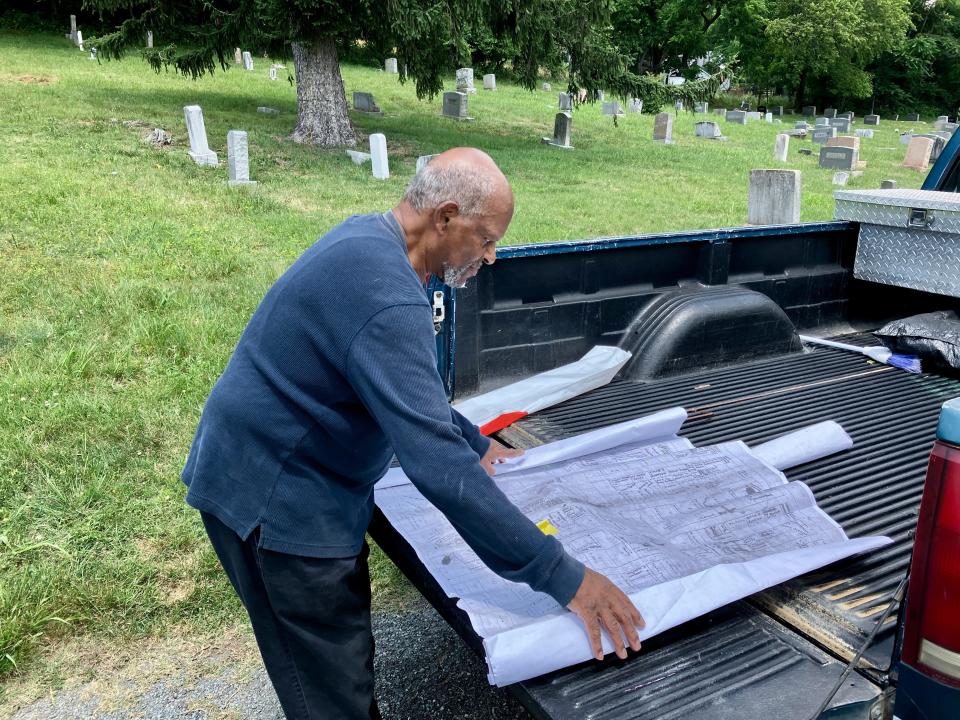

Charles Cubbage, 75, is a member of Augusta Street United Methodist. He is one of two people who help as caretakers, in charge of cemetery mapping. Cubbage was born and raised in Elkton before moving to Staunton after serving four years in the United States Marine Corps. As a member of his church, he began helping the former caretaker and, two years ago, took over the job.

When someone needs to be buried at Fairview, or if a family member is looking for a grave, Cubbage is the man who is called to help. On a recent Wednesday afternoon, he took out his carefully rolled up map of the cemetery and spread it out on the back of his pickup truck, explaining just how he matches the figures on the map with the database of names to locate gravesites.

As he walked around Fairview, he pointed out where Arthur R. Ware Jr., a former educator who has his name on a Staunton elementary school. Cubbage also pointed out the gravesite for William and Queen Elizabeth Miller, an African-American couple who ran an orphanage in the western part of the city for nearly 40 years until fire burned it to the ground in 1955.

Who will take over the job when he’s no longer able to do it?

Cubbage paused for a few seconds when asked the question before simply answering, “I don’t know.”

Maybe having an administrative office located in a restored Shea House will ensure that information like Cubbage has will not be lost in the future. And it’s crucial that Staunton preserves that information and history.

“The experiences of those who are laid to rest right there in Fairview tell a larger national story,” Tillerson-Brown said. “Integration, segregation, Jim Crow … we can add to our understanding of those important events with evidence of from some of those experiences of folks that are laid to rest in Staunton in Fairview Cemetery.”

More: Lake Anna outbreak: Virginia Department of Health update

More: ‘Humbling, heartwarming’: Community Foundation celebrates nonprofit grant recipients

— Patrick Hite is a reporter at The News Leader. Story ideas and tips always welcome. Contact Patrick (he/him/his) at phite@newsleader.com and follow him on Instagram @hitepatrick. Subscribe to us at newsleader.com

This article originally appeared on Staunton News Leader: Save Shea House: Fundraiser planned to restore Fairview Cemetery cottage

Signup bonus from