Eight miles into the Grand Canyon, legs flung over the front tube of the raft, I was still dry, gaping at the way 40 million years of geologic history have compressed into a few thousand feet. Watching the sky shrink as the walls got higher, I was lulled into a kind of complacency by the heat and the river’s rhythm. Then came the drop into the edge of Badger Creek Rapid. A wall of water washed over the front of the boat, stopping us, soaking us and spitting us out. A river can change your mind pretty fast.

I’ve been a river runner since I was an 18-year-old rookie raft guide, stringy-armed and reedy-voiced. In a boat, I learned that rivers give you power, but only once you find the line between holding your angle and falling into the flow — an act easier said than done. Moving downstream lets you feel connected to everything around you. That’s a feeling I’ve been chasing ever since, numinous and hard to name.

I am 40 now, and sometimes I feel far from the person who went to the river that first time, ready to dive into the unknown. Now, I have a mortgage and a garden. I have achy, stitched-together joints, and I sit in front of a computer most days. My life feels too soft, too superficial, too fast and smooth. I’d been missing that edge and missing the river.

So I signed up to be a swamper, a glorified intern on a commercial trip, working for free because I’d given myself the idea that the best place to re-immerse myself was here, in the Grand Canyon, the pinnacle of American river trips. I wanted to see if I could still be the girl who would throw herself into the waves, watching the bubble line for clues. I wanted to remember why it felt so good, and I’d decided this was the place. That first splash brought me back.

If you were just to look at geographic stats, the Grand Canyon might not seem that grand. It’s not the biggest canyon in the world, nor the deepest or the longest. It’s not even the biggest canyon in its own basin; Desolation Canyon upstream is deeper. But here, the razor blade of the river cuts through a billion-year history of rock, revealing all of our existence and more.

Humans have used the Grand Canyon for 13,000 years, since the last ice age, and the river flows through the region’s cultural history. “Our ancestors had always told us not to forget that the middle of the river is the backbone of the people,” Hualapai tribal member Loretta Jackson-Kelly told the Grand Canyon Trust. “Without the backbone, we cannot survive.” Hualapai say the native fish in the river are their ancestors; everyone says that the water is life.

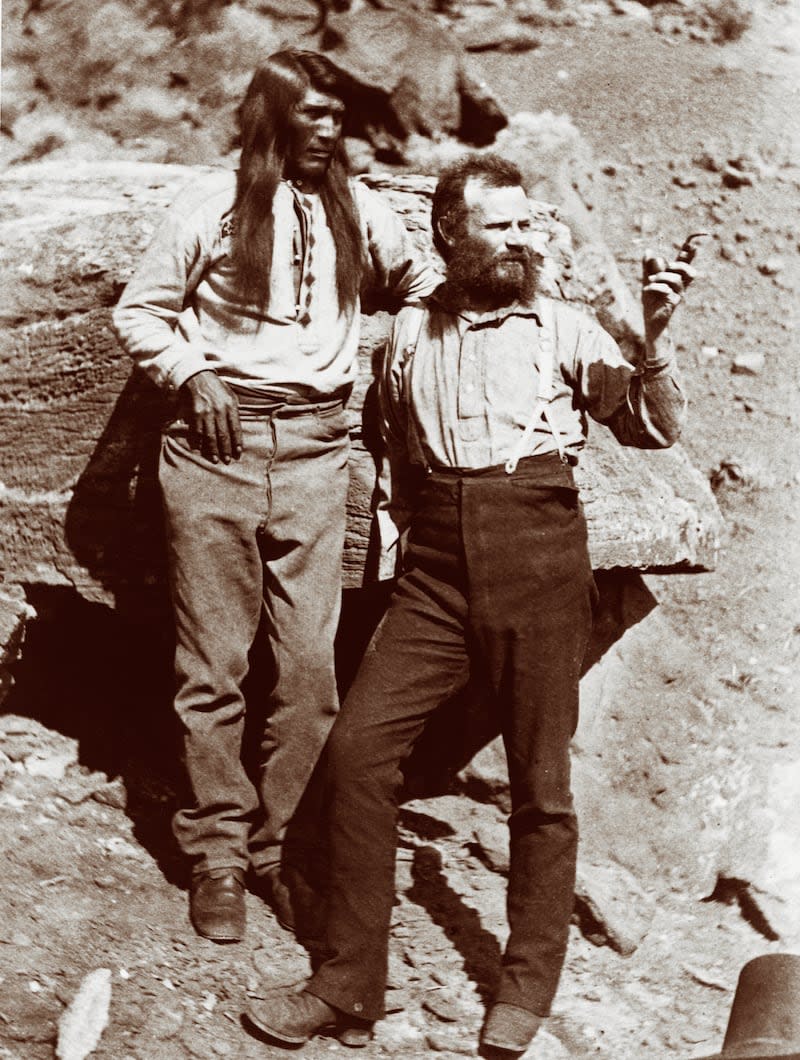

Hopi say that a boy named Tiyo, who was searching to understand the river, was the first person to travel down the San Juan and Colorado rivers, into the Sea of Cortez. He returned with the story of the rain dance and helped break a long drought. Colonial Western history pegs the first successful trip through the Grand Canyon as the Powell Geographic Expedition of 1869. Before Maj. John Wesley Powell led a group of nine men down the Green and Colorado rivers, recording the geology and geography along the way, the canyon was the last great unmapped section of the country. From their perspective, no one had ever made it through alive before. Powell lost three men along the way, but he made it back with maps.

Whichever story you hold true, the common ground is that there weren’t many people floating the river before the middle of the 1800s, and it took another 100 years for anyone to do it with any regularity. The Colorado River through the Grand Canyon was epic, dangerous, beautiful.

It became a touchstone for why we go to wild, adventurous places, and the harms we enact when we do. The curve of recreation in the country is mapped out here, from exploration to attempted extraction to a rush of adventure.

But even with that focus on action, Nikki Cooley, the first-ever Navajo river guide, says we can’t think of it like a theme park. The river, which is dammed above and below the canyon, is a fragile, frangible place: It’s in a national park, heralded as pristine wilderness. But it’s also severed by those dams, threatened by mining and drought — hoisting a patchwork of adaptive management plans and the misplaced good intentions of past lives up between it all. The river is the backbone of so much, and rafting is a way through.

On the water, days become ritualistic: the hours on the water, the thunk of oars, the Zen work of unpacking and repacking your home every day on a different slanted beach. Morning stretching, afternoon hikes up side canyons, evening drinks, the way we all grip tight when the rapids ramp up. The river moves in an S-curve south and west. Every night we are deeper in. Every day I see something I didn’t even know to look for.

The only other time I’ve been here in the gut of the gorge, I was running rim to rim to rim, down to the river, back up, then reverse. On the trails down from the rim, you cut a quick line through all the layers, feeling yourself drop down through time, and then pulling yourself back up. Now I’m moving on the other axis, through instead of across.

In a boat, you move at the pace the river sets, the canyon unspooling in front of you, layer by layer, changing color and pitch. In the slow water days, like when we float through Furnace Flats, time compresses, and I have time to read about the people who came through before me.

The first women to successfully make it through the canyon weren’t looking for thrills or isolation; they were looking for plants. Lois Jotter and Elzada Clover, two botanists from the University of Michigan, were trying to record unknown species. Clover had met Norm Nevills, an early river guide, on a previous research trip. Nevills, who had been running other rivers in the basin, had never seen the Grand Canyon before, but he wanted to, and he wanted attention for it, so together they hatched a plan to paddle through. Their trip became a precedent for the future: in the way they ran the river, in the biological record they captured, in the fact that women could handle the canyon — an idea that had previously been dismissed. Journalist Melissa Sevigny, who recently wrote a book about their groundbreaking trip, “Brave the Wild River,” said the two were surprised by how powerful the river was, but they were also shocked by its beauty and range. They thought the river might be “barren and hellish,” but instead, they cataloged 400 species of plants. “Clover wrote about how she’d been told the canyon was this dark, gloomy place,” Sevigny told me. “I think she fully expected to experience that, but found it not to be the case — she formed a very deep connection with the canyon and the river and wrote eloquently of its beauty.”

The trip changed their perception of the place, and their perceptions of themselves. Years later, Jotter — who, among other feats, spent a night stranded alone on a high water beach — would still talk about the boost of confidence that came from facing the river, and her own capabilities in the face of it.

“Our ancestors had always told us not to forget that the middle of the river is the backbone of the people. Without the backbone, we cannot survive.”

I am a little jealous of that trip, and of how much was unknown when they set off. In some ways, that feels far away right now, when nearly everywhere is mapped, geotagged, Google-able. But you can never really know a rugged place, or know how you’ll respond, until you’re in it, shoulders and hands hardening, a form of personal erosion. To learn what Jotter did, I think you have to feel the friction in your body.

By the end of the first week, I have heat rash and Velcro fingertips. New muscle deep in my elbows aches from rowing, and layers of my skin slough off, exfoliated by the spackle of sunscreen and sand. Sometimes the wind blows so hard that we’re basically floating backward. We carry on, somewhere between uncomfortable and entranced.

When we spend a night at Big Dune Camp, the river, which had been clear and greenish from dam runoff, turns red from flash flooding. It runs thick, the color of terra cotta. It’s how the river would have been before the dam went in and held back all the sediment behind its walls.

Sand is the story of how the dam stops time, changes the ecosystem, strips it bare. Even this camp is a remnant of the unnatural balance struck between these walls.

Last spring, after a big winter of snow, the Bureau of Reclamation decided to conduct what it calls a high flow experiment. The bureau sent a big pulse of water out of Glen Canyon Dam, intending to mimic historic high flows. That water ripped through the canyon, flushing out debris, setting off native fish spawning cycles, and rebuilding beaches, including the eponymous big dune here. It’s been destroyed and poorly rebuilt by hydraulic engineering, as has so much else in this protected canyon we hold up as the highest level of wilderness. It’s one thing to know that, intellectually. It’s another to see it happen. When you’re outside in a landscape where you can feel the erosion and see the river change, you’re forced to confront it. Contact leads to understanding and incentive to take care of the place. It makes it real. The grit makes the good parts shine.

One midmorning, we hike into a waterfall up clear blue Shinumo Creek. We dive under the spray, swimming into the cool green cave behind the falls, rinsing the grit out of our hair and our eyes. Tiny threatened native humpback chub tickle our toes. They have a stronghold here. It seems like every side canyon holds a secret or a story like that. I think you could come through a million times and still keep stumbling on newness. It’s not just the rapids and the big water rush that make it magic, like I had thought it might. Instead, it comes from the details and from having the time to let them sink in.

Psychological research has found that feeling small and independent in a big place is good for our brains. A 2018 study from UC Berkeley found that awe, more than any other positive sensation, gives us a full spectrum sense of well-being, which can help people recover from PTSD, anxiety and a wash of other stressors. The Berkeley researchers monitored the stress hormones of veterans and at-risk teens who spent time outside and found that stress hormones significantly lowered when they were on river trips.

The awe sneaks up on you. It’s the weight of the oar in my hand and how I learned the river by figuring out the feeling of water on a blade. It’s how I now know what bighorn sheep look like silhouetted on the ridge, the ram in full curl. And how I know what happens when you follow the track of a tiny scorpion and find it under a rock, translucent and mad. It’s that balance of working hard and letting go. Meeting the river and letting it move you.

Once you get addicted to that alchemy, you are never far from the canyon in your mind. There will be rapids running through your dreams, cutting through tapeats and travertine. Some people get it so bad that they’re always trying to get back, unable to let go, sucked into the mythology and the movement.

People and their stories stipple the myths. Nels Niemi, who died in October, rowed it 178 times, starting in 1967. In the days before the National Park Service started regulating trip length, he spent over 100 days straight on the river, connecting the Snake, the Green and the Colorado, making a home of the canyon. He’d been down there so much he knew exactly where to find sun in December.

My life feels too soft, too superficial, too fast and smooth. I’d been missing that edge and missing the river.

Seth Mason, a member of the U.S. men’s rafting team who made several attempts to set the speed record through the canyon, says the team spent obsessive years training, trying to memorize every rapid so they could run it in the dark. “For us, the pull had a lot to do with the lore and this rich history of people chasing crazy ideas down there,” he told me.

They didn’t break the record. One time, the flows weren’t high enough. On another attempt, they busted up their boat at Lava Falls, mile 179 of 277, trying to run through the gnash of whitewater in the dark. A reminder that the river is in charge.

The rapids aren’t necessarily the best part of the river, but they keep you honest. All trip, I had an underlying stomach churn about the biggest rapids: Crystal and Lava Falls, wondering how they would go. Lava is the last big rapid and it looms over everything. There’s an adage in the Grand Canyon that you’re always above Lava, even off the river.

I’d been worrying, and then suddenly we were above it. Standing at the scout for the rapid, watching the water pile up over the thundering ledge hole at the top, funnel down toward the Big Kahuna wave and slam the Cheese Grater rock on the right. Some of the famous rapids in the Grand aren’t tricky, they’re just big, but Lava is both technically difficult and huge. It’s the epitome of the river’s power. You can feel the force from shore. And you have to make it through Lava to make it through the canyon.

We ran left at Lava, hitting the edge of the guard wave at the top and then skirting the edge of the huge central hole. Our boat captain, Kelly, pushed hard on the oars, punching through the huge sloshing waves to the end till we came out clean. I rode the bull on the nose of the boat, clenching the chicken line with both hands, screaming, laughing in the troughs of the waves. Feeling that teenage rush moving through me once more.

And then, just like that, we were above Lava again, regrouping on the beach below, already thinking about next time. Wrung through a range of emotions, lit up and feeling it all: the aliveness and ache, the alignment of all things, the focus. We were buzzing down to our toes. “The Grand Canyon is not just a joy ride. It is an entity,” Niemi once said in the Boatman’s Quarterly Review.

I understand why you’d want to be here hundreds of times over, and I think that rush and release is a worthy thing to chase. Science, like that Berkeley study, backs that up, and so do the lessons of our lives. It doesn’t necessarily have to be here, in this particular canyon, but there’s some sort of need for wild places, disconnection, sand between our teeth, to feel alive and part of the flow. It can’t last forever. In a week I’ll be home, back in the garden, the emotional antipodes of the Grand. But I’ll still have the grit on my skin.

This story appears in the June 2024 issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.

Signup bonus from