The year was 1951. And in Macon, Georgia, an excited group of students were celebrating their graduation from Ballard-Hudson Senior High School, an institution designed by pioneering architect Ellamae Ellis League.

Among the proud graduates was an 18-year-old student who had traveled the country a bit as a child thanks to the train passes issued by Central of Georgia Railway — her father’s employer. This student had already designed her own life plan, which entailed leaving the South behind for a northern destination more than 800 miles away.

That student — known then by her maiden name, Bernice Farmer — is Bernice Laster today. And the chosen city up north that the daughter of Perry and Willie May Wembley Farmer set her sights on moving to, even prior to her high school graduation, was Detroit.

“I was born in the South, but I wanted to go to school and receive the training and skills that would allow me to be an entrepreneur, or pursue some other job that was not domestic work,” said the now 91-year-old Laster, who was encouraged to move to Detroit to attend Wayne (now Wayne State) University by her history teacher at Ballard-Hudson which back then had an all-Black student body due to forced segregation. “In the South, as a Black woman, even with training, you were not going to get opportunities because all of the store jobs and government jobs, and any kind of jobs, went to privileged white women. But my mother and grandmother instilled in me to want more in life, so I was glad to leave home for an opportunity to try to give myself a better life in Detroit.”

However, before Laster could begin executing her plan, she first needed to make her way from the Macon, Georgia, train terminal to an imposing location in Detroit’s Corktown neighborhood that once housed a three-story depot with 10 gates for trains, connected to an 18-story tower with more than 500 offices.

“I remember walking through that station; buildings like that you didn’t see everywhere,” Laster regaled as she recalled her earliest thoughts about the Michigan Central Station, Detroit’s primary railway depot from 1913 to 1988, and a onetime gateway to Detroit for thousands of daily rail passengers from across the country. “I was excited when that train stopped in Detroit. But as Black people living during those times, we didn’t carry ourselves in public just any kind of way as we do now. Everywhere you went, you were always concerned about your safety.”

Laster’s statement reflects the views of someone whose early life experiences were shaped not only by a segregated society, but also by the violence that came with it. The violent treatment of Black people in the South often had a lasting impact on future generations, such as the infamous July 25, 1946, Moore’s Ford lynchings, described by some as “the last mass lynching in America,” which resulted in the killing of two Black married couples — George W. (a World War II veteran) and Mae Murray Dorsey, along with Roger and Dorothy Murray (in her seventh month of pregnancy) — by a white mob at Moore’s Ford Bridge in Walton County, Georgia, about 80 miles north of where Laster grew up.

“You talk about segregation, they knew how to segregate in those days. But despite segregation and all of our struggles connected to it, our mothers still found a way to raise families and educate their children,” said Laster, who spoke Sunday evening from her home in northwest Detroit. “Some of these women even built colleges; and they filled up your belly. My mother and grandmother always saw to it that we had plenty to eat and that was very important. Before we left home, we would have biscuits, grits, salt pork and eggs that they prepared in the morning. That’s how we started every day.”

As Laster tells it, the crammed shoebox containing mouth-watering fried chicken that she took with her on the train while heading north was just a small sampling of the physical, mental and spiritual nourishment she had received from her family, which Laster would need to successfully make a new home in Detroit. For example, when money was needed to continue her education after completing a semester at Wayne, Laster called on lessons she had learned in and around the kitchen back home to secure a job as a cook and a waitress at Bonner’s Kitchen on Davidson and Dequindre. And the money she made at the restaurant helped her pay for classes at Highland Park Community College, where she ultimately earned an associate’s degree. There would be more jobs for Laster, too, including a nurse’s assistant position at Henry Ford Hospital.

Then, in 1964, Laster accomplished something that she believed would have been impossible for her to do had she not boarded a train to Detroit after completing high school: She landed a “good, government job” with the U.S. Postal Service.

“It gave me the opportunity to work and make a living wage,” said Laster, who was hired as a distribution clerk at Detroit’s main post office at 1401 W. Fort St. “That was one of the greatest things that ever happened to us.”

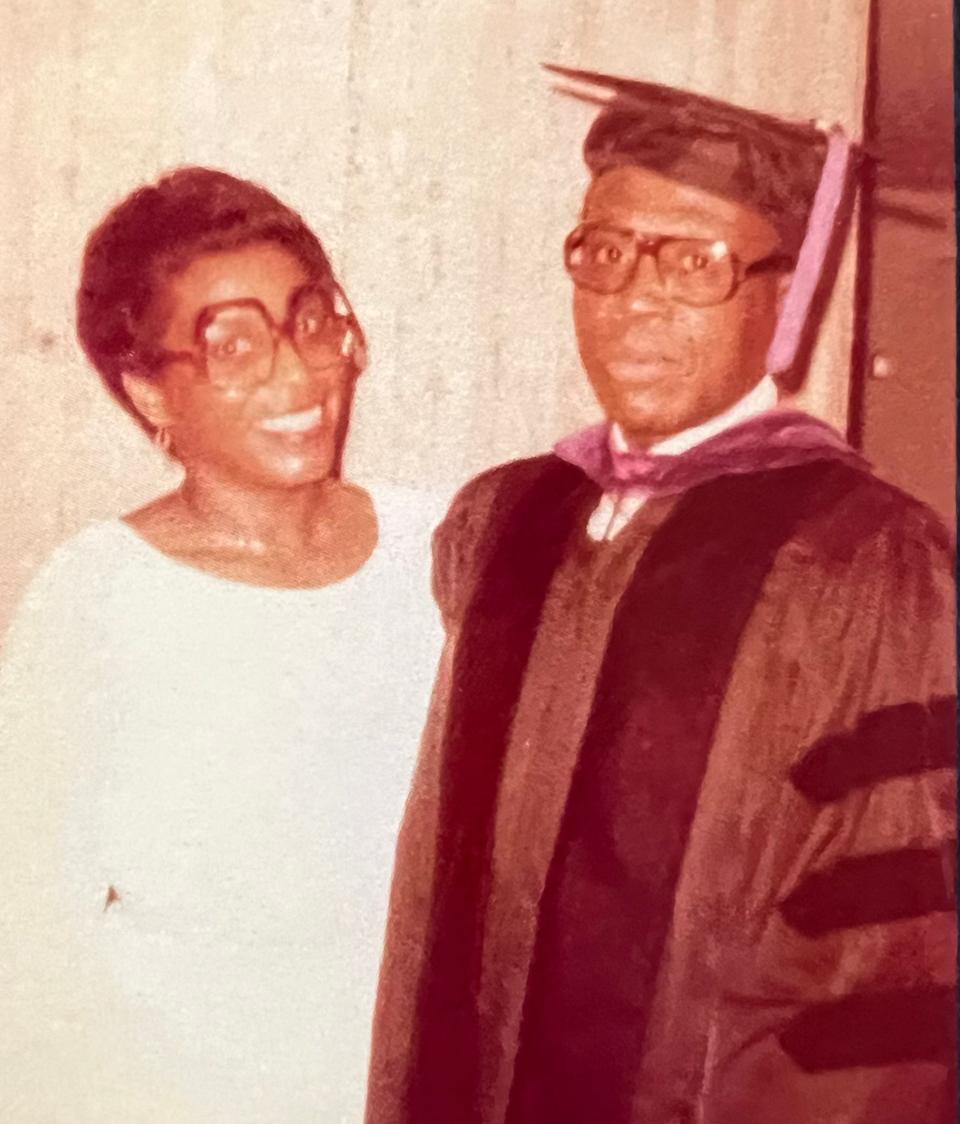

The “us” that Laster was referring to in that instance was the life partnership she shared with the late Ernest Laster, her loving husband for 58 years, and the person who validated Bernice Laster’s decision to come to Detroit in the grandest way possible.

“I was blessed that the Lord sent me someone to love, and the Lord sent me a man who loved me,” Laster, who married Ernest three months before starting work at the post office, beamed. “When we were first getting to know each other, he asked me to ride out to Belle Isle, and who would refuse going out to Belle Isle? From that point on, he just worked everything to perfection.”

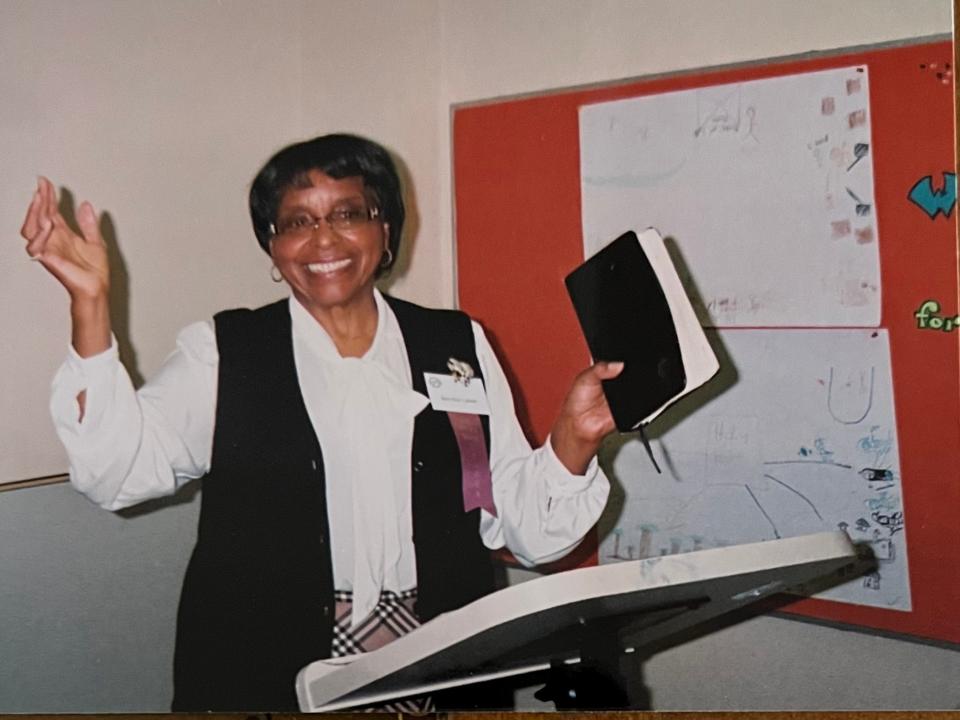

And with plenty of love in her life, Laster said it was not difficult for her to work 27 years at the post office, where she retired in 1981 as a mid-level supervisor. After completing her government work, Laster then was able to fully focus on providing service to her community, particularly youths, which she happily performed by teaching Sunday school and vacation Bible school at Hartford Memorial Baptist Church for 18 years.

In recent years, Laster has touched the lives of metro Detroit youths through outreach she has performed with Boys & Girls Bible Clubs and Child Evangelism Fellowship. It is work that Laster still continues today and does not plan to give up anytime soon — however, she confided that she is looking forward to taking a little break. And during that “break” she said she expects to return to a familiar site with a few close friends to take part in the reopening celebration at Michigan Central Station that is taking place through June 16.

“After moving to Detroit, it was always exciting to catch the train to visit family back home, and I’m excited about being invited to go down to the station for the reopening,” said Laster, whose knack for offering encouragement to others throughout her life extended to her husband, who she encouraged to go to law school, which he successfully completed. “The physical strength and energy that God gives you is amazing and I used it to have a good life in Detroit. But nothing we did here in Detroit was us — it was all the Lord.”

Scott Talley is a native Detroiter, a proud product of Detroit Public Schools and a lifelong lover of Detroit culture in its diverse forms. In his second tour with the Free Press, which he grew up reading as a child, he is excited and humbled to cover the city’s neighborhoods and the many interesting people who define its various communities. Contact him at stalley@freepress.com or follow him on Twitter @STalleyfreep. Read more of Scott’s stories at www.freep.com/mosaic/detroit-is/. Please help us grow great community-focused journalism by becoming a subscriber.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: As a teen in the South, train rider chose Detroit for her home

Signup bonus from