The historic Eastern Kentucky coal town of Lynch could face fines for environmental violations so high they would threaten the city’s viability.

That was one blunt message at a meeting this week on how to fix sewer treatment shortfalls in Cumberland, Benham and Lynch, in Harlan County.

The three cities were chosen for a federal pilot program aimed at helping communities facing economic hardship deal with failing sewer systems.

The sewer plant in Lynch was built nearly 70 years ago and has not functioned properly for several years, releasing “minimally treated” sewage that fouls water quality in Looney Creek, according to an assessment.

“The Lynch system is in very bad shape,” Rebecca Goodman, secretary of the Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet, said at a public forum Tuesday.

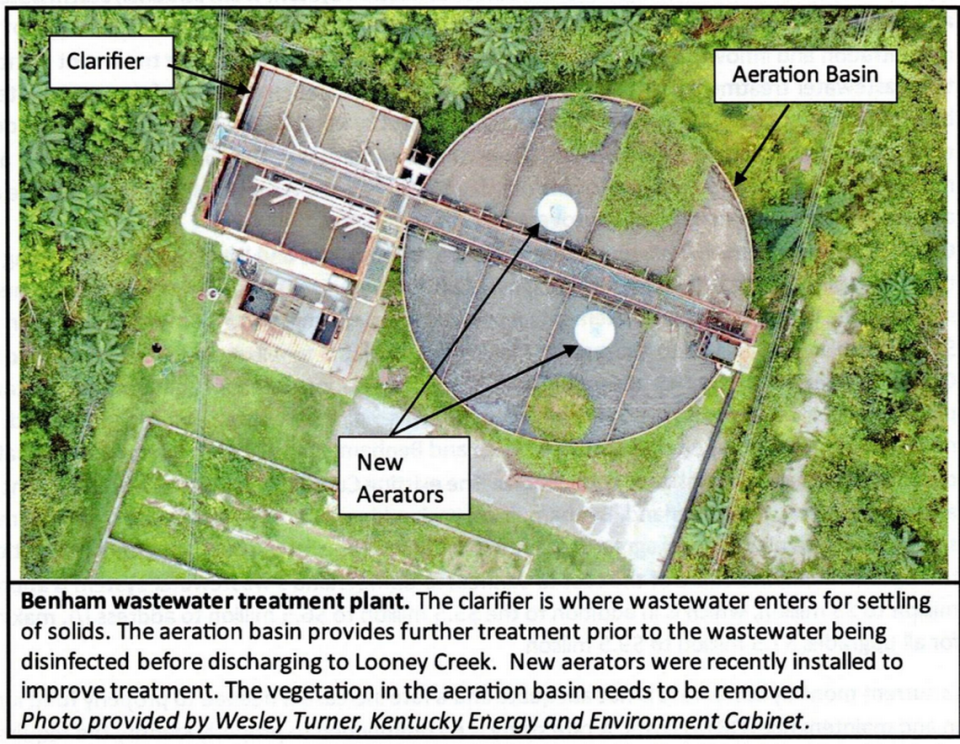

The wastewater systems in Cumberland and Benham are in better shape, but state regulators have cited all three cities for violations.

Authorities advise against contact with the water in Looney Creek, which runs from Lynch past Benham to Cumberland, and into the Poor Fork of the Cumberland River, which Looney Creek enters, Goodman said.

The three towns near the state’s highest peak are trying to promote tourism in order to create jobs, but sewage treatment shortcomings are an impediment, Cumberland Mayor Charles Raleigh said.

“If they want to go kayaking or fishing,” he said of visitors, “they don’t want to be told there’s poop in the river.”

In a court motion in April 2022, the Energy and Environment Cabinet argued Lynch had not completed repairs to its water and sewer plants and should have to pay a penalty of $5.8 million.

The city’s attorneys said in a response that since Justin Wren took over as mayor in 2021, Lynch had worked to secure money for upgrades to the plants and had received $140,000 from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) for the work.

A penalty of $5.8 million would “permanently quash” the city’s operations, its attorneys said in the response.

The lawsuit was later put on hold, but the cabinet could move to put it back on the front burner.

Goodman said state inspectors have cited hundreds of additional alleged violations at Lynch since the state first sued the city. The maximum penalty for those would be $29 million, she said.

Lynch has a budget of over $626,000 for the upcoming fiscal year, according to City Clerk Tiffany Scearse.

Goodman acknowledged a judge is not likely to order the maximum potential fine against the city.

But the cabinet, charged with protecting the environment, can’t allow violations to continue indefinitely, Goodman said.

“I’m not after the penalty. I’m after compliance,” she said.

Where would the money come from?

The discussion of potential penalties against Lynch was in the context of exploring options to fix sewer problems in the three towns.

The three were among only 11 locations in the U.S. chosen to receive free assessments and technical assistance under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act, which the Biden Administration pushed in 2021.

The program, which is under the the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, also could help the cities get federal money to fix their sewer systems.

The Kentucky Rural Water Association and the Rural Community Assistance Partnership also are working with the cities under the program.

State and federal officials held a meeting in Benham this week to present information on potential plans for fixing sewage treatment in the three cities, along with estimates on the costs and rate increases that would be required to pay for the work.

Janet Cherry, an environmental engineer who assessed the systems, identified a number of options, including building a new sewer plant in Lynch and upgrades to the existing plants in Benham and Cumberland.

Whatever else happens, Cherry said, all three cities need to first fix a problem they have with rainfall and groundwater infiltrating the sewer systems through manholes and cracks in decades-old clay collection tiles, which increases treatment costs and can top the treatment capacity of the plants.

State and federal officials would prefer that all three towns take part in one system, arguing that would lower the cost of operating and maintaining sewer systems and increase the likelihood of getting grants for improvements.

Officials presented details on only two options at the community meeting for the cities to combine sewer service.

Both would require Benham and Lynch to pump their untreated wastewater to the larger plant in Cumberland — which has adequate capacity if all three cities fix the infiltration problem — and pay a fee for treatment.

Under either plan, Benham and Lynch would abandon their sewage treatment plants.

That’s been a sticking point.

Before the community meeting on Tuesday, Raleigh and Benham Mayor Danny Quillen said they had agreed in principle for Benham to send its wastewater to Cumberland for treatment.

Lynch had not yet signed on, however.

“They’re trying to force it down our throats,” Wren, the Lynch mayor, said of the regional concept.

Wren said he would prefer to get funding to fix collection lines and rehabilitate Lynch’s sewer plant.

Scearse said the city has paid off about $108,000 in debt since Wren took office in mid-2020, and Wren said he has worked on improving the sewer system and applied for a number of grants.

One concern with sending Lynch’s waste to Cumberland is that the city would lose revenue, Wren said.

After a further meeting with officials, Wren told the Herald-Leader on Thursday that Lynch will adopt a resolution agreeing to discuss the possibility of a joint sewer system with Cumberland and Benham.

Wren said he hopes to keep rates “as cheap as possible for the residents.”

Other officials said it’s unlikely state or federal agencies would approve funding for Lynch for a standalone sewer project, in part because of its small population.

In 2020, the population of Lynch was 658. Cumberland had 1,947 residents and Benham had 512 in the 2020 Census.

Quillen said it has been a struggle for Benham to maintain its sewer system because of a lack of revenue.

All three towns have been hurt by a loss of coal jobs, which plunged beginning in 2012, and a loss of residents.

Loss of coal jobs has impacted revenue

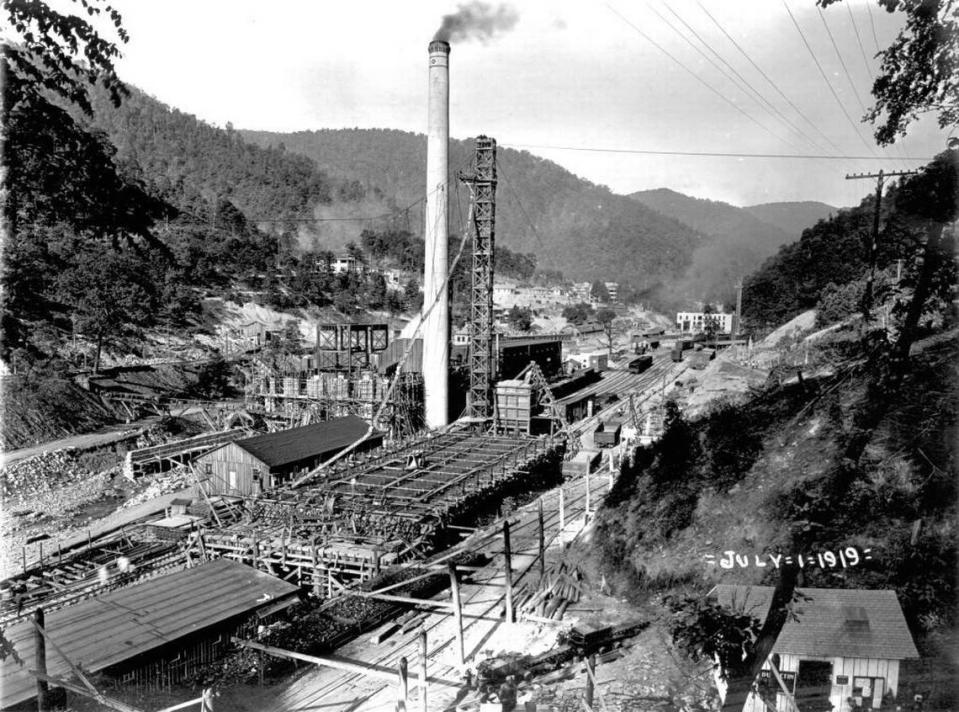

Coal was the lifeblood of the towns for decades.

International Harvester, needing coal for its manufacturing operations, built Benham beginning in 1909 in what was then a remote valley at the foot of the state’s highest peak, Black Mountain.

A few years later, in 1917, U.S. Steel began building Lynch a little further upstream on Looney Creek, creating a company-owned town to serve its mines, with hundreds of houses, schools, churches, a hospital and hotel.

With a population that peaked at about 10,000, Lynch was the biggest coal town in the world at one time.

Cumberland was settled in the 1830s and grew as a trading center in the area.

The coal companies gave up ownership of Benham and Lynch decades ago, selling the houses to residents.

The three cities are strung together over a distance of six to seven miles. It doesn’t make sense anymore for them to continue trying to operate separate sewer plants, Quillen said.

“This is a golden opportunity for us,” he said of the chance to get funding for an improved system under the federal infrastructure law. “You can sit around and let the problem get worse or you can do something now.”

Raleigh said he has worked to improve the Cumberland sewer plant, ordering equipment off eBay at times and doing the installation himself to save money.

The plant is in good shape, but the city hasn’t been able to fix its infiltration problem, he said.

“When they’re putting all this money in here, why would you not want to jump on it?” Raleigh said.

Raleigh said Benham and Lynch would probably save money by sending their waste to Cumberland instead of paying for the employees, chemicals and electricity to run their own treatment plants.

Would all of this mean higher rates?

All the options for fixing the sewer systems in the three towns would require higher rates, even if they didn’t develop a shared system, according to estimates by Cherry.

Cherry said the customer charge for operation and maintenance of the Lynch system as of last November was $38.58 a month for the first 2,000 gallons.

That would increase to $64 to $80 to cover operations, maintenance and loan repayments under one plan for a three-city system operating under an interlocal agreement, and $54 to $65 under another option in which the cities would turn over their systems to a new, joint sewer agency, she estimated.

The sewer operation and maintenance charge to customers in Benham was $31 for the first 2,000 gallons as of November. That would increase to $61 to $77 under an interlocal agreement for a joint system and $54 to $65 under the option of creating a new, outside sewer agency, Cherry estimated.

Those estimates assume the systems receive grants under the federal infrastructure law to cover 75 percent of the cost to fix their collection lines and do other work to link the systems, and loans for 25%.

However, officials said the cities could qualify for grants from other sources that would push down the amount they would have to borrow.

The goal would be to get 100% grant funding, Raleigh said.

Several people at the meeting raised concerns about rate increases because many people in the area have low or fixed incomes.

But officials said residents face higher rates even if the cities don’t develop a shared system.

For instance, Cherry estimated fixing the collection system and building a new treatment plant in Lynch would cost up to $12 million, requiring a rate increase.

Harlan County Judge-Executive Dan Mosley urged the cities to move together on a sewage-treatment plan, saying funding under the federal infrastructure law could be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

“We want to see Looney Creek clean,” Mosley said. “We owe it to our kids and grandkids not to squander this opportunity.”

Signup bonus from