Marvin DeWitt became the Henry Ford of the turkey industry. Like Ford, he experienced poverty.

Marvin’s great-grandfather, Gerrit S. DeWitt, was a farmhand in the Netherlands. In 1848, when he was 17 years old, he immigrated to West Michigan, where he spent his first night under a shelter of boards he had assembled along the Black River.

Discovering there was no paid work available in Albertus Van Raalte’s colony, he migrated to Kalamazoo, where he again worked as a farmhand. While there, he would occasionally visit friends in Holland; one year he traded a horse for 40 acres of land in Fillmore Township.

While boarding in Kalamazoo, he met Mary Meijaard. She had emigrated from the Netherlands in 1847 with the Van de Luyster, Steketee, and Van Der Meulen-led Zeelanders. After marrying in Zeeland in 1854, Gerrit and Mary lived on a lawyer’s farm near Kalamazoo.

In 1856, they moved to their property in Fillmore Township. But to farm, they first had to clear the land: Gerrit chopped down trees such that they would fall into heaps; then between the heaps they planted corn and potatoes. While living in Fillmore they worshiped with Albertus Van Raalte’s congregation. In 1866, they and their nine children joined Ebenezer Reformed Church.

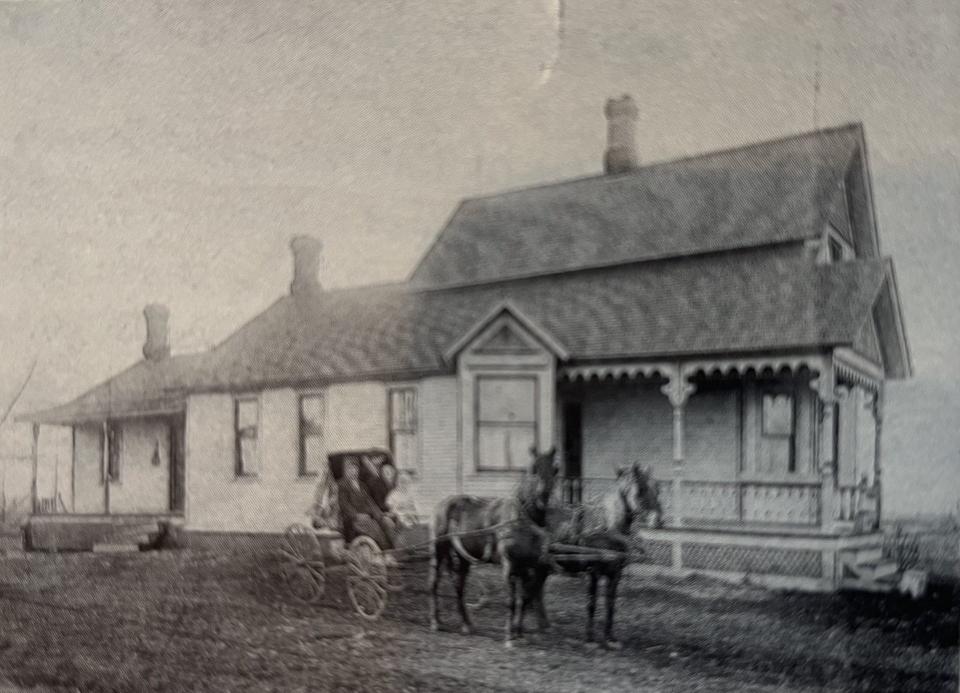

Marvin’s grandfather, George, was born in Fillmore Township. He married Anna Boeve. George and Anna had three sons, eventually helping them purchase parcels of land. Marvin’s father, Gerrit, chose property on 96th Avenue north of Borculo.

There, Gerrit and his wife, Susan Van Den Berge (whose family owned a dairy farm on 16th Street east of Holland), started their own farm. Gerrit and Susan had six children, including their youngest, Marvin, born in 1919.

But Gerrit had health issues that prevented him from doing farmwork. So, in 1923, Gerrit and Susan moved their family to Zeeland, so he would be closer to factory jobs. Eventually, they purchased a house on Lincoln Street.

In 1927, when Marvin was eight years old, he took home some culls — disfigured and discarded chicks — from a nearby hatchery, housed them in his family’s barn, fed them oatmeal and water, warmed them from the heat of a light bulb, and adopted them as pets. He saved enough money working odd jobs to purchase a box of healthy chicks, then raised 60 laying hens and sold their eggs for cash, saving some of the money and contributing the rest to the family’s rainy-day fund.

Meanwhile, Marvin’s older brother Bill worked various jobs. One of his jobs was cleaning at Frank’s Restaurant in Zeeland. Later, Marvin would follow in Bill’s footsteps, selling ice cream bars during summertime band concerts in Zeeland’s van de Luyster Square for a vendor who operated a peanut and ice cream business out of a converted Model T Ford.

Marvin also sold magazine subscriptions door-to-door, and baked goods.

The Stock Market Crash of 1929 and Great Depression saw Gerrit not only lose his job, but $3,000 he’d borrowed against his Borculo property to invest. Because the family lacked the resources to buy farming supplies, equipment, and livestock to start over, the DeWitts moved to the Rudyard area in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula to live with relatives. There, they worked as farm hands. Meanwhile, in 1932, the bank foreclosed on their house in Zeeland.

Moving to Rudyard meant Marvin had to transfer schools. Wishing to be done with school, when the teachers asked him about his grade level, Marvin convinced them to put him not in the seventh grade, but the eighth grade. A few weeks later, his transcripts arrived from Zeeland. They said otherwise.

In the spring of 1933, the DeWitts were solvent enough to move back to Borculo. There, on their farm, they grew pickles for Heinz and sugar beets for the Holland Sugar Company, and eggs, milk, meat, and produce for their own sustenance.

Still, living on the farm wasn’t as nice as living in the city. Unlike their home in Zeeland, the farmhouse in Borculo didn’t have central heating or an indoor toilet, and it didn’t have electricity until 1936. Using a small washtub, the family took stand-up sponge baths. Because washing clothes was difficult, they wore their clothes — mostly handmade — until they were stiff from dirt and perspiration.

Marvin had to return to school. We’ll tell more of his story next time.

— Steve VanderVeen is a resident of Holland. You may reach him at skvveen@gmail.com. His book, “The Holland Area’s First Entrepreneurs,” is available at Reader’s World.

This article originally appeared on The Holland Sentinel: Holland History: Marvin DeWitt and life on the farm

Signup bonus from