It’s understandable that we often look upon people from prior eras and assume they experienced less enjoyment than those of us with running water, insulated homes, and endless entertainment. Yet in different ways, modern Americans seem to have lost some of the capacity to experience simple joys often taken for granted in the past.

This is especially apparent in journal and newspaper accounts from the pioneer holiday season, which were examined in a 2001 BYU Studies article by professor Richard I. Kimball. These stories demonstrate at least five ways where the early Utah settlers enjoyed simple pleasures during the Christmas season that seem to be lost on many Americans today.

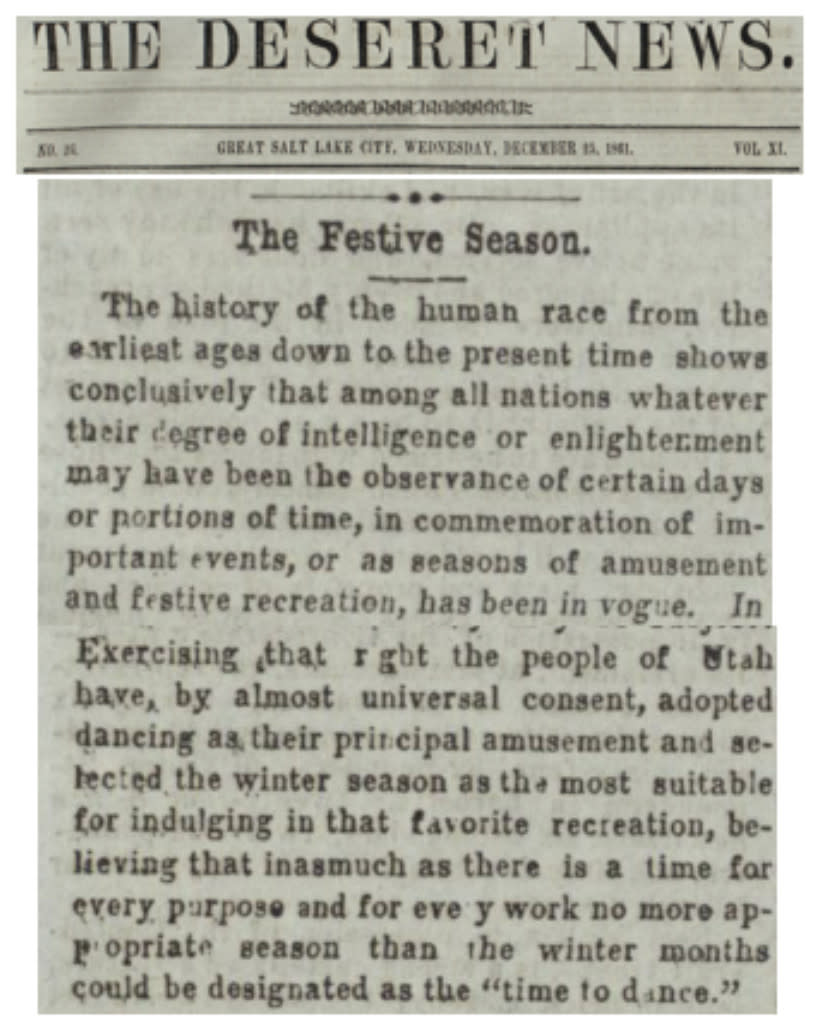

1. Dancing. Dancing was almost universal in early holiday gatherings — from intimate family settings to larger church and community parties. On Christmas day in 1861, the Deseret News issued a statement on the place of dancing in Latter-day Saint holiday culture that, Kimball notes, sounded almost like “an official decree.”

“In the observance of anniversaries and holidays … every nation, kindred, tongue and people have notions peculiar to themselves, suited to their political, religious and social existence, and particularly in the choice of amusements,” the statement read. “Exercising that right the people of Utah have, by almost universal consent, adopted dancing as their principal amusement and selected the winter season as the most suitable for indulging in that favorite recreation.”

Even on their first Christmas in 1847, the pioneers gathered at John Rowberry’s home in Tooele and danced to Cyrus Call’s whistling until midnight, since no one owned a musical instrument in the settlement.

On the second Christmas in the valley, Catherine Wooley recollected in her journal about 17 couples she hosted for a dancing party ate refreshments first at 8 in the evening, and then again at 1, and 3 a.m. in the morning as they danced all night.

An even bigger group congregated at Brigham Young’s home on Christmas in 1850, with 150 guests eating and dancing “until a late hour.” An 1852 report described a “mammoth” dancing party in Salt Lake City involving hundreds of people across two days, and lasting on the second day from 10 a.m. in the morning until midnight.

For readers beginning to wonder whether these early dancers were getting a little out of the control, the Deseret News at the time felt similar. The paper’s editors wrote in 1865 that dancing is a “good and healthy exercise when it is not indulged in to excess and when proper precautions are taken to avoid injurious results,” adding, “no wise person would wish to dance every evening.”

2. Singing. Various kinds of singing also occupied early settlers during the holidays, well beyond the congregational singing of hymns. In the early years, accompaniment was limited to violins, banjos, and guitars — with the first piano arriving in Utah in 1851.

A brass band reportedly traveled by horseback throughout Salt Lake City on Christmas morning in 1850, serenading various citizens and leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Another part of the 1852 Christmas party Brigham Young hosted was hours of singing and listening to speeches late into the night.

3. Speaking and performing. Public speeches were commonly reported as sources of enjoyment and entertainment. Women gathered at the Willis home to hear religious and philosophical instruction between Christmas and New Year’s. Parley P. Pratt gave a talk at the time titled “The Velocity of the Motion of Bodies When Surrounded by a Refined Element.”

For those less drawn to dance, Utah’s long-standing tradition of theater also provided a welcome alternative. The newly renovated Salt Lake Theater reopened its doors on Christmas Eve in 1862 with a “crowded house at the Theatre.”

4. Simple sweets. Like Latter-day Saints today, forbears relished a good feast. Christmas Day in 1847 found Eliza R. Snow at a party hosted by Lorenzo Young, where around a dozen guests “freely and sociably partook of the good things of the earth,” including a “splendid dinner.”

While holiday celebrations included diverse culinary traditions around the world, their recipes remained relatively simple. That included Scottish shortcake, Danish “sweet soup made of rice and fruit juice” and Scandinavian rice mush cooked in milk and sweetened with cinnamon and sugar.

British Saints enjoyed simple plum pudding, with handcart pioneer Ann Mailin Sharp journaling about her holiday treat consisting of “flour, suet (animal fat), molasses, dried groundcherries, and a few dried wild currants” all boiled together for hours.

By the second Christmas in the valley, there was enough molasses stored to make candy canes for the children, along with honey taffy and animal-shaped cookies from sweet dough for filling Christmas stockings.

At Brigham Young’s 1850 feast, a donation of candies and raisins arrived from one Capt. Hooper, which were divided among the poor.

5. Sitting and visiting. The winter months meant slow agricultural times in the state, with harvest over and the ground generally too hard to plow. The Deseret News commented in 1865 on the coming Christmas time, when “workmen are taking the holidays, because they can’t help it.”

“Good fires are pleasant just now,” the article stated. “Remember the poor, where you find them, you who are comfortable; their comfort will add to your pleasures.”

This time to rest was a source of relief to people accustomed to long days of manual labor. That same 1865 Deseret News editorial noted how much more “leisure time” was “at the command of the people than at any other season of the year,” permitting a welcome period of “very general relaxation from arduous toil.”

An 1869 editorial in the Juvenile Instructor commented on the winter holidays providing “long evenings for social gatherings and parties and pleasant fire-side” discussions, suggesting that “in no country and among no people are they more valued than in our Territory and by the Saints who reside here.”

The Deseret New reported in 1865 that three days after Christmas, Brigham Young and a number of family members and friends were sighted “out sleigh driving on Monday, in that mammoth sleigh, with some others of a smaller calibre in the wake.”

The historical record documents the care early Saints took to not mix celebrations with worship, as celebrations were deemed more “fitting to be performed” on a weekday than “on the Sabbath.”

Making merry even in difficult conditions. Holiday rest and relaxation wasn’t always possible, of course. Elizabeth Huffaker recalled the first Christmas in 1847 where her family “all worked as usual that day.”

“The men gathered sage brush, and some even plowed, for though it had snowed, the ground was soft and the plows were used nearly the entire day,” she wrote. Despite simple commemorations, including a Christmas dinner of boiled rabbit and bread, Huffaker later remarked that “in the sense of perfect peace and good will I never had a happier Christmas in all my life.”

Even during that first Spartan winter in the valley, Susa Young Gates recalled with fondness the “organiz’d parties” held around the season, including one she and Eliza R. Snow attended together with friends at Brother Writer’s home, where Snow journaled they “had a good time.”

The festivities didn’t stop after New Year’s Day was over for some early Saints. On Jan. 5, 1854, the Deseret News reported that the Social Hall, then Salt Lake City’s largest gathering place, “has been occupied every afternoon and evening … by social parties; changing daily, and (vying) with each other which shall enjoy themselves most, while each in their turn have seemed to be full, enjoying all they were capable of.”

Something valuable can be learned from these early settlers and Saints and the delight they took in simple pleasures. It’s fair to say that if there were a head-to-head holiday competition that spanned the generations — “vying which shall enjoy themselves most” — it’s possible an upset victory might go to early settlers, even without running water and modern insulation, but in securely in possession of humble human joys.

Signup bonus from